Gearing up to publish a poetic memoir celebrating connections to poetry throughout my life, my relationship with the art form, and my attempts to use it and the lessons I’ve learned to professional advantage, I am compelled to share an illustrative example of the meaningful book of poetry.

My own bookshelves have held many such volumes over the years, and in leading up to the release of “Arc of the Poet,” I am pulling them down, dusting them off, and sharing some comments on their spellbinding charms.

Why do some old books of poetry fire me up? This 1886 edition was the first I brought home. Mr. Longfellow wrote magical lines about Hiawatha, inspiring generations, including Mom, my brother, and me. #Poetry drew us in, and sparked our imaginations. #amwriting #writerslife pic.twitter.com/wQnNZxrBFR

— Roger Darnell (@RKDarnell) September 26, 2022

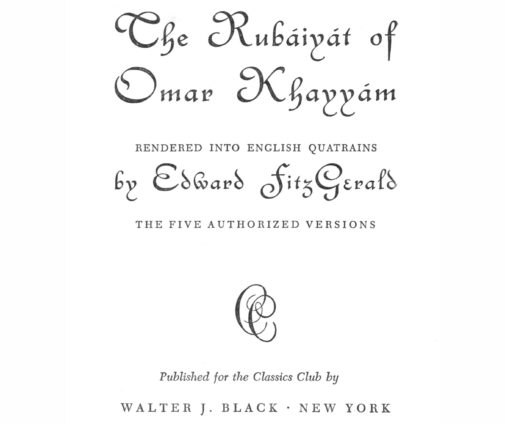

Preparing that list, one book was inadvertently overlooked, and when I noticed the error, the warm sensation of sparked creativity rushed through my veins. This collected treasure is actually not one volume but two: I have “The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám – Rendered Into English Quatrains by Edward FitzGerald” published for the Classics Club by Walter J. Black, copyright 1942 … and also, “The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám” illustrated by Jeff Hill, published by The Peter Pauper Press in 1950.

To make my case for the publication of creative work according to one’s best ideas and capabilities as opportunities arise, I will draw liberally from the Classic Club edition’s introductory chapter entitled Edward FitzGerald and the Rubáiyát, by Gordon S. Haight. If you are imagining something dusty and lifeless, prepare for a shock.

. . .

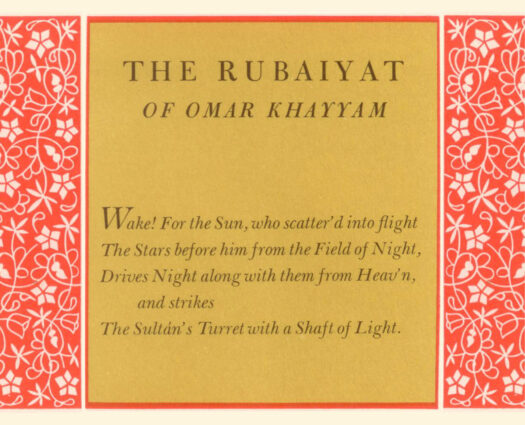

“In 1861 a bundle of pamphlets was placed on a second-hand bookstall in London for clearance at a penny apiece. They bore the title Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám, the Astronomer-Poet of Persia, Translated into English Verse, but nothing to indicate that they were the work of Edward FitzGerald. Quaritch, the bookseller, had printed two hundred and fifty copies for the author, who gave a few to his friends and, when it became apparent that there was no demand for the book, presented his publisher with the rest. The original price of five shillings having been reduced to one without effect, they were finally consigned to the penny shelf – the last stage before books become waste paper.

“They might very well have suffered this ignominy but for two young men, later to be famous as poets, Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Algernon Charles Swinburne. Hearing of the book by chance, they each bought several copies at a penny; when they went back the next day for more, they found that the price had doubled. Enthusiasm for the Rubáiyát spread quickly through the circle of their friends, and within a week or two, according to Swinburne, the remaining copies were being offered at twenty-one shillings, and later “at still more absurd prices.” How amazed he would have been to know that in 1929 a single copy of the pamphlet in its humble brown paper cover sold for $8000!”

. . .

“The Rubáiyát will always attract some readers by its dark philosophy. In sending a copy to a friend FitzGerald wrote: ‘It is a desperate sort of thing, unfortunately at the bottom of all thinking men’s minds, but made Music of.’ The music – the essential poetry – gives the work its real eminence. Swinburne, who was a good judge of such matters, called it ‘that most exquisite English translation, sovereignly faultless in form and color of verse.’ On these virtues it will stand forever with the greatest literature.” – Gordon S. Haight

. . .

It is remarkable to read of how this work was ultimately received around the world, especially in the post-Civil War era by Americans. As an artist, I was highly intrigued to learn so much from Mr. Haight’s account. The original work is reportedly much less curated, and not rated highly among Persians. In fact, FitzGerald is credited with selectively curating his chosen content to introduce a novel form, as well as wholly inventing the majority of what his book “renders.”

With this far-fetched example of a bygone literary pursuit that was one simple thing when it took form, and by chance, became a global phenomenon, I rest my case for the merits of publication. My own contributions may soon become waste paper, and yet, fate may also introduce some other possibility. In a 1986 poem entitled “Now Now,” I set down a catchy line about creating something in a second that holds the future of my past. Perhaps Mr. FitzGerald, whose esteemed friends included Alfred Lord Tennyson, might have fancied that.